Our hope is that this blog will become a forum in which people can exchange ideas on how to recruit, develop and retain exceptional Jewish educators through mentoring and e-mentoring students, teaching candidates, and teachers in our day and supplemental schools. The present focus of this blog is to empower Jewish teachers, administrators, teacher trainers, consultants, and staff developers to integrate web technology (i.e. web tools and apps) into their teaching and teacher training.

Send Richard a voice mail message

Friday, October 30, 2009

Instructional Method to Empower Students to Create Their Own Questions for Small Group and Whole Class Discussion: The Q-Matrix of C. Wiederhold

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Sample Questions Applying F. Lyman’s Think-Trix for Student-Generated Questions

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Instructional Method to Empower Students to Create Their Own Questions for Small Group and Whole Class Discussion: Think-Trix (Lyman, 1987)

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about instructional methods to empower students to generate their own questions. One of those methods is the Think-Trix of * Frank Lyman(1987).

Frank Lyman, Ph.D. created the Think-Trix visual cues as a device to prompt students to create their own questions for classroom discussion and inquiry. These visual cues are designed to empower students to ask seven different types of questions. On the top of this post is a chart depicting the seven visual Think-Trix cues.

*Lyman, F. (1987) The Think Trix: A Classroom Tool for Thinking in Response to Reading. In Issues and Practices. A Yearbook of the State of Maryland International Reading Association Council. 4, 15-18.

On the next post we will share a chart showing sample questions applying Frank Lyman’s Think-Trix.

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Description and Application of Think-Pair-Share: A Cooperative Learning Procedure for the Judaic Classroom

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about the Cooperative Learning Model of Teaching.

One example of a cooperative learning procedure for the Judaic classroom is Think-Pair-Share (*Lyman, 1981, 1992). A description of this cooperative procedure and a sample application for the Judaic classroom follows:

Think-Pair-Share: This is a three-step paired cooperative procedure. During step one, each member individually and silently thinks about a question posed by the teacher. During the second step, two members are paired to exchange and discuss their responses. During step three, each member may share his response, his partner’s response, a synthesis or something new with the quad, another quad, or the entire class. Participants always retain the right to pass or not share information. There are many variations including: Think-Write-Pair and Share and Think-Web, Pair-Web and Share.

Sample Applications: (1) Instead of posing a question to the class, the teacher uses Think-Pair-Share. (2) The teacher poses this question to his or her class: Think of your favorite biblical hero or heroine; Pair (discuss) with your partner; Share your answer with the class.

*Lyman, F. (1981). The Responsive Classroom Discussion: The Inclusion of All Students. Mainstreaming Digest. University of Maryland, College Park, MD. Lyman, F (1992). Think-Pair-Share, Thinktrix, and Weird Facts: An Interactive System for Cooperative Thinking. In Enhancing Thinking Through Cooperative Learning. Davidson, N. & Worsham, T. (Editors). NY: Teachers College Press, 169-181.

On the next post we will describe and give a sample application of another cooperative learning procedure, Pairs.

Group Discussion with a Timer: An Interactive Method to Facilitate A Classroom or Small Group Discussion

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching.

One interactive method to facilitate a classroom or small group discussion is Group Discussion with a Timer. An explanation of the rules for engagement follows:

Group Discussion with a Timer

The teacher poses a question or problem to the class. Each member is given time (e.g. 30 seconds) to compose a response to the teacher’s question. Each student is then given a period of time (e.g. 60 seconds) to share his or her response with the class. The teacher selects a student to serve as a timekeeper to let each speaker know when the designated time has elapsed.

On the next post we will discuss instructional methods to empower students to generate their own questions for classroom discussion.

Monday, October 26, 2009

Listen to the Podcast in which Richard Solomon Explains the New 8 Stage Career Development Ladder for Jewish Educators

Group Discussion with Nominal Brainstorming: An Interactive Method to Facilitate A Classroom or Small Group Discussion

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching.

One interactive method to facilitate a classroom or small group discussion is Group Discussion with Nominal Brainstorming. An explanation of the rules for engagement follows:

Group Discussion with Nominal Brainstorming

Note: This form of brainstorming does not require a time limit; however, a class recorder is needed.

· The teacher poses a question, and each student spends a short period of time, e.g. 60 seconds, thinking of and recording solutions to the problem posed.

· In a round robin fashion each student shares one new or different solution to the problem.

· Students may pass if they have no new or different solution to offer.

· When all the students pass three times, nominal brainstorming ends.

On the next post we will share another small group or whole class discussion procedure called Group Discussion with a Timer.

Friday, October 23, 2009

Group Discussion with Brainstorming: An Interactive Method to Facilitate A Classroom or Small Group Discussion

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching.

One interactive method to facilitate a classroom or small group discussion is Group Discussion with Brainstorming. An explanation of the rules for engagement follows:

Group Discussion with Brainstorming

This is a structured group discussion procedure where the rules for brainstorming are followed. The general rules for brainstorming are as follows.

· You may say anything that comes to mind during the allotted time limit (determined by the teacher or the group).

· You may repeat or modify the ideas previously presented.

· You may not discuss, praise, criticize, or reject the ideas presented.

· Select someone to record the ideas suggested.

· Evaluate ideas after brainstorming is completed.

On the next post we will share another small group or whole class discussion procedure called Group Discussion with Nominal Brainstorming.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

You’re the Teacher: An Interactive Method to Facilitate A Classroom or Small Group Discussion

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching.

One interactive method to facilitate a classroom or small group discussion is You’re the Teacher. An explanation of the rules for engagement follows:

The teacher poses a question to the class. After some wait time has elapsed, e.g. 10 seconds, students raise their hands indicating that they want to share some information. The teacher then invites a student to speak. After the student has completed her response, she becomes the teacher (i.e. discussion leader), and then selects the next student to speak.

On the next post we will share another small group or whole class discussion procedure called Group Discussion with Brainstorming.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Group Discussion with Paraphrase Passport: An Interactive Method to Facilitate A Classroom or Small Group Discussion While Improving Student Listenin

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically grounded best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about Group Discussion with Paraphrase Passport, an interactive method to facilitate a classroom or small group discussion while improving students listening to each other. An explanation of the rules for engagement follows:

A student may share information if he or she first accurately paraphrases the previous speaker. However, if the student does not accurately paraphrase, he or she is corrected by the student who spoke previously. Thus, paraphrasing is the passport for group discussion.

On the next post we will share another small group or whole class discussion procedure called You’re the Teacher.

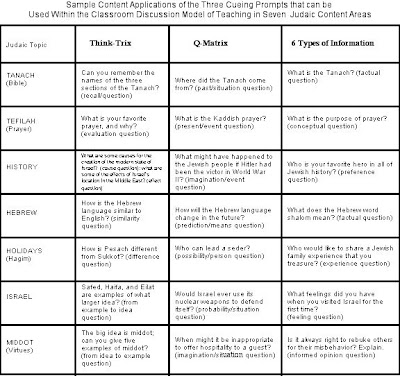

Content Applications for Three Visual Cueing Prompts (i.e. Think-Trix, Q-Matrix and the Six Types of Information) for Student Generated Questions

The chart at the top of the post presents some sample questions that students can pose during a classroom discussion. Note how the three visual cueing prompts (i.e. Think-Trix, Q-Matrix and the Six Types of Information) can be applied across seven Judaic topic areas.

On the next post we will begin our discussion of the second student-engaged model of teaching, Cooperative Learning.

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

Group Discussion with Talking Chips: An Interactive Method to Facilitate A Classroom or Small Group Discussion

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching.

One interactive method to facilitate a classroom or small group discussion is Group Discussion with Talking Chips. An explanation of the rules for engagement follows:

Group Discussion with Talking Chips

Materials needed: Each member of the group has a talking chip or token (e.g. a pen, a pencil, a crayon, a checker, a name tent, etc.)

The members of each group are engaged in a structured exchange of information. The rules for sharing information are as follows; a member may make a statement, or raise a question only after he or she has placed his or her talking chip in the center of the table. Members may not share additional information until the chips of all the members have been placed on the table. If a participant chooses not to speak, he or she must place his or her chip on the table, and say, "I pass." After all members have spoken or passed, participants retrieve their chips from the center of the table. Any member may begin talking provided that he or she places his or her chip on the table. Group Discussion with Talking Chips can be used for a whole classroom discussion as well.

On the next post we will share another small group or whole class discussion procedure, Group Discussion with Paraphrase Passport.

Monday, October 19, 2009

The Discussion Ball: An Interactive Method to Facilitate A Classroom or Small Group Discussion

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically grounded best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching.

One interactive method to facilitate a classroom or small group discussion is the Discussion Ball. An explanation of the rules for engagement follows:

The Discussion Ball

Materials Needed: A small, soft rubber, nerf, or koosh ball.

Students are seated in a circle, and a discussion ball is placed on the floor, or on a table. After a question for class discussion is posed by the teacher, students are given some wait time, e.g. 20 seconds, to compose a response. In order to speak, a student must first take possession of the discussion ball. Upon completing his or her response, the student must replace the discussion ball on the floor or on the table.

On the next post we will share another small group and whole class discussion procedure, Group Discussion with Talking Chips.

Friday, October 16, 2009

Application of the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching with a Lesson on Precious Jewish Memories

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly our mentees should know about the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching.

Now let’s insert into the five-step Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching template a whole classroom discussion on favorite Jewish memories.

The Five Steps of the Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching

Steps | Description | Teacher and/or Student Behavior |

1 | Get students ready to learn, and clarify the objective/s for the discussion | · Teacher gets the students ready to learn by saying, “Today we are going to discuss some of our favorite Jewish experiences.” · Teacher identifies the objective/s for the discussion by saying, “Therefore, the objective for today’s lesson is to share one precious Jewish memory. For example, one of my poignant memories was the time...” |

2 | Focus the discussion | · Teacher provides the focus for the small group discussion by saying; |

3 | Facilitate the discussion | · Teacher invites students to share one poignant memory with the class. Students who wish to share their precious memory raise their hands, and the teacher selects the order for sharing by using the Numbers Method. See the explanation of the *Numbers Method below. |

4 | Terminate the discussion | · Teacher brings closure to the discussion saying: “Isn’t it interest to learn what different precious Jewish memories we possess?” |

5 | Reflect on the discussion | · Teacher invites students to share their thoughts and conclusions by saying, “I want you to complete this sentence stem; One thing I learned from today’s lesson is …” |

*The Numbers Method

The teacher poses a question to the class. After some wait time has elapsed, e.g. 10 seconds, students raise their hands indicating that they want to share something. The teacher then assigns each class member a number identifying the order for sharing information.

On the next post we will share another whole class discussion procedure, The Discussion Ball.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

The Classroom Discussion Model of Teaching: A Student-Engaged Model of Teaching

Steps | Description | Teacher and/or Student Behavior |

1 | Get students ready to learn, and clarify the objective/s for the discussion | · Teacher gets students ready to learn. · Teacher identifies the objective/s for the discussion. |

2 | Focus the discussion | · Teacher explains the ground rules for the discussion. |

3 | Facilitate the discussion | · Teacher facilitates one of the whole class or small group discussion procedures described below. |

4 | Terminate the discussion | · Teacher brings closure to the discussion. |

5 | Reflect on the discussion | · Teacher invites students to share their thoughts, and conclusions about the discussion content and discussion procedure. |

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

What are the Major Differences Between the Teacher-Directed and Student-Engaged Models of Teaching?

When mentoring our pre-service and in-service teachers we need to describe and model both research-based and clinically tested best practices. Accordingly, our mentees should know some of the major differences between student-engaged and teacher-directed models of teaching.

Some Major Differences Between the Student-Engaged and

the Teacher-Directed Models of Teaching

Student-Engaged Models of Teaching | Teacher-Directed Models of Teaching |

Teacher structures many opportunities for students to talk. | Teacher does most of the talking. |

Teacher invites students to help create meaningful classroom rules. | Teacher promulgates the classroom rules. |

Students create knowledge. | Teacher transmits knowledge. |

Students construct knowledge. | Students receive knowledge. |

Teacher respects the prior knowledge of students, and views students as theory builders. | Teacher views students as empty vessels having little relevant prior knowledge. |

Teacher taps into the multiple intelligences of students. | Teacher primarily uses visual and auditory means to deliver instruction. |

There are many teachers, and learners in the room. | There is one teacher in the room, and many learners. |

Teacher and students pose questions to the entire learning community. | Teacher poses the questions. |

Teacher uses traditional, and non-traditional, or alternative assessment instruments. | Teacher primarily uses traditional assessment instruments. |

Teacher gives students raw data, primary sources, and manipulatives to generate the major concepts in the curriculum. | Teacher tells the major concepts in the curriculum. |

Teacher allows student responses to drive the lesson. | Teacher's lesson plan drives what is taught each day. |

Teacher provides students with many opportunities to interact with one another, and move around the classroom. | Teacher believes students must be still in order to learn. |

On the next post we will begin our discussion of the first student-engaged model of teaching, the Classroom Discussion Model.

Jewish Education News Blog

Richard D. Solomon's Blog on Mentoring Jewish Students and Teachers

http://nextleveljewisheducation.blogspot.com/

-

Dad, for the win.11 months ago